Labour and Labour Welfare is of critical importance since it directly deals with the livelihood of working people. Kerala has responded to the need for labour welfare and development very differently from the national economy, especially in the context of globalisation. The State has increasingly followed a rights-based approach to the changing needs of the labour market. The policy initiative of the government seeks the overall growth and development of both the industry and the individual worker who have equally contributed to the progress of the State. Workers in Kerala have been protected through the consistent intervention of the Government in respect of the right to engage in work of one’s choice, right against discrimination, prohibition of child labour, social security, protection of wages, redressal of grievances, right to organize and form trade unions, collective bargaining and participation in management. The Government is of the view that every employee/worker should be a member of a Welfare Board and must be protected by the State throughout their lives. Currently around 32 Labour Welfare Fund Boards exist in the State, of which 16 are under the Labour Commissionerate.

In spite of achieving adequate level of growth rate since 2002-03, Kerala faces important challenges in the labour sector in terms of high rates of unemployment and under employment, a low rate of productive employment creation, inadequate levels of skill creation and training, low level of labour force participation and a smaller worker population ratio. On the whole, the State has to create employment opportunities and employment-intensive growth. The labour force must shift from low-value added to high-value added activities. The State aims to achieve a job-induced growth in the economy to create new jobs in both urban and rural Kerala, a unified and consolidated legislation for social security schemes, re-prioritisation of allocation of funds to benefit vulnerable workers, long term settlements based on productivity, labour law reforms in tune with the times, amendments to the Industrial Disputes Act,1947 and a complete revamping of the curriculum and course content in Industrial Training Institutes. Monitoring and Evaluation have also been considered integral to labour reforms against the backdrop of increasing inter-State and international migration.

Daily Wage Rate

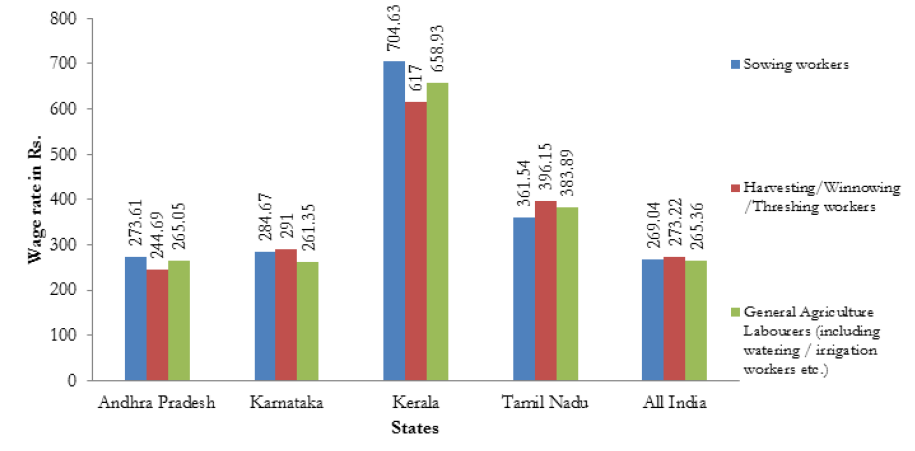

The reported wage rate of workers in the agricultural and non-agricultural sectors in Kerala is higher than in other States. The average daily wage rate of agricultural and non-agricultural workers in India published by the Labour Bureau, Government of India shows that for male general agricultural workers in rural Kerala it is 658.93 in July 2017. The national average for this category of workers is only 265.36. The wage rate in Kerala is thus higher than the rest of the country by a factor of 2.5. Figure 4.3.12 shows the average daily wage rate of male agricultural workers in rural areas as compared to the national average and the average across the southern States.

Source: Ministry of Labour and Employment, GOI

Source: Ministry of Labour and Employment, GOI

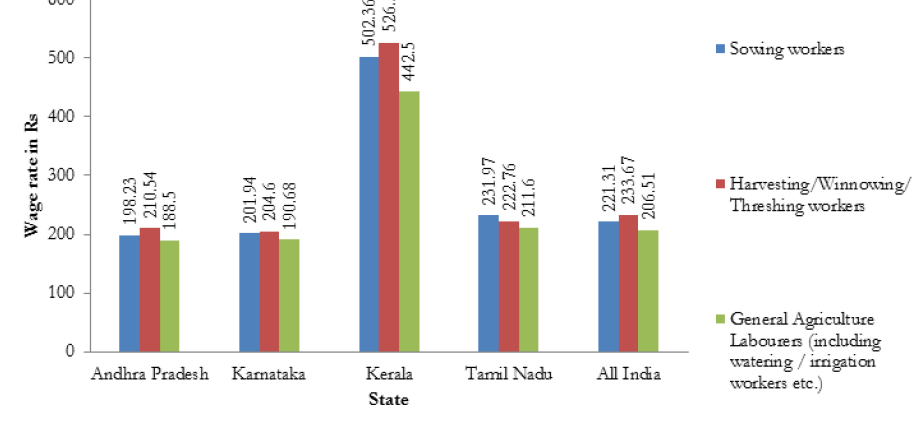

With respect to female agricultural workers in rural Kerala, the average daily wage rate in July 2017 is 442.5 compared to the national average of 206.59. The wage rate for sowing and harvesting workers in Kerala are 502.36 and 526.53 respectively, compared to the national average of 221.31 and 233.67. A comparison of the daily wage rates of female agricultural workers in southern States is given in Figure 4.3.13.

Source: Ministry of Labour and Employment, GOI

Source: Ministry of Labour and Employment, GOI

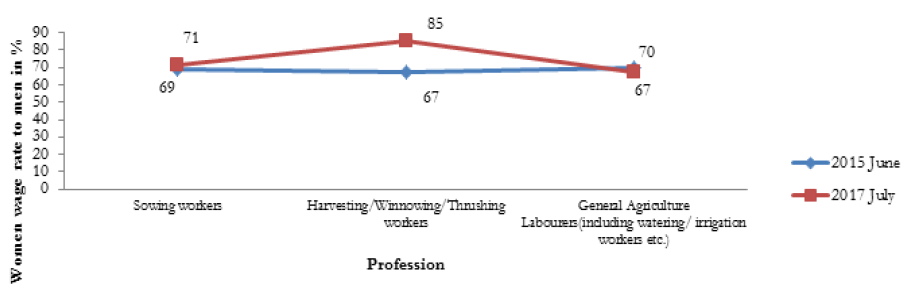

Even though the wage rates of agricultural labourers in rural Kerala are higher than the wages in other parts of the country, the wage disparity between male and female workers is quite significant. The male-female wage gap among the rural workers engaged in general agriculture is 33 per cent with the wage rate for the female worker being 67 per cent of the male workers’ wage rate. Figure 4.3.14 shows the male-female difference among agricultural workers in Kerala and other southern States of India.

Source: Ministry of Labour and Employment, GOI

Source: Ministry of Labour and Employment, GOI

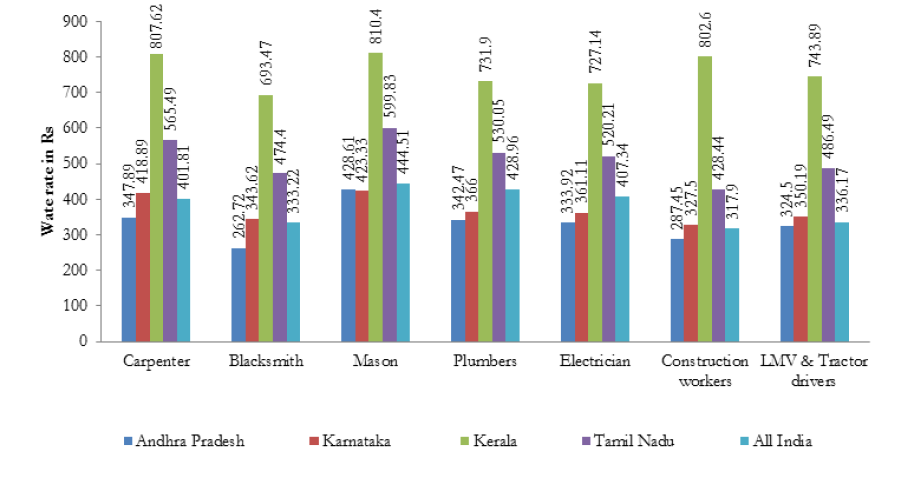

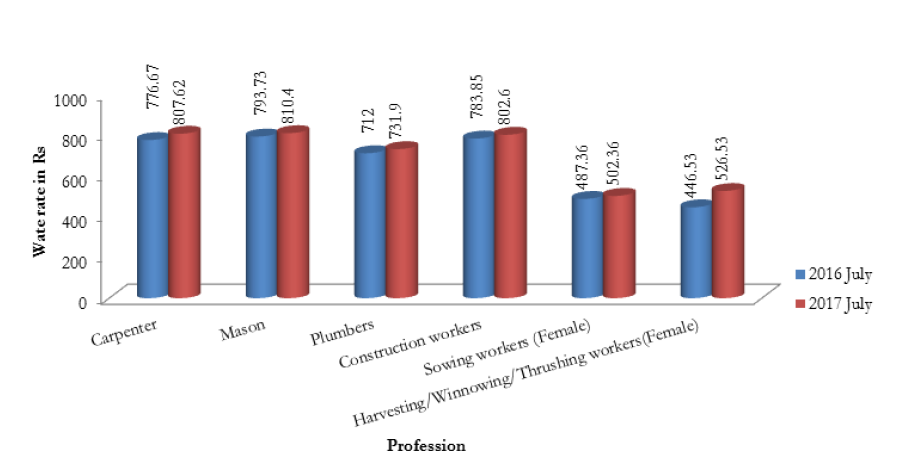

The average daily wage rates in Kerala are much higher than the minimum wage, and this attracts in -migrants into the State, especially from areas where wage rates are very low. Further, the wide disparity in male-female wage rates is an indication of the fact that the perception of gender equality is far from being realised. The average daily wage rate of non-agricultural workers in rural Kerala in July 2017 is shown in Figure 4.3.15. Wage growth in Kerala for the period July 2016 to July 2017 is given in Figure 4.3.16.

Source: Labour Bureau, Ministry of Labour and Employment,GO

Source: Labour Bureau, Ministry of Labour and Employment,GO

Composition of Workers

The labour community in Kerala mainly consists of those who are engaged in the informal sector (loading and unloading, casual work, construction work, brick-making, self-employment, etc), the traditional industries (coir, cashew, handloom, beedi-making, etc), the manufacturing sector (small, medium and large industries), the IT industry, the units in export promotion zones and those who are seasonally employed.

Industrial Relations

Healthy relations between employer and employee are the key to sustained industrial development. The responsibility of the Labour Department is to aid in this and to help maintain a harmonious balance between the labourers demands and the management in order to maintain an atmosphere conducive to achieving the objective of industrial growth and prosperity in the State.

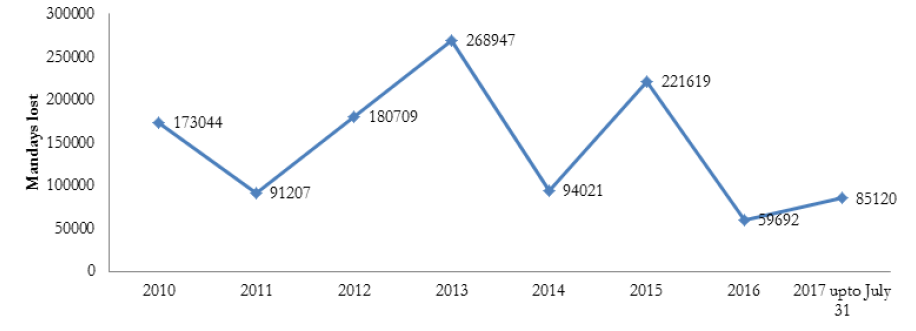

The strikes of labour in the State has reduced significantly over the years. The man-days lost due to strikes in the State for the year 2017 (up to July) was 85.12 thousand as against 2.68 lakh in the year up to July 2013. Figure 4.3.17 shows the mandays lost due to strikes in Kerala.

Source: Labour Commissionerate, GOK.

Source: Labour Commissionerate, GOK.

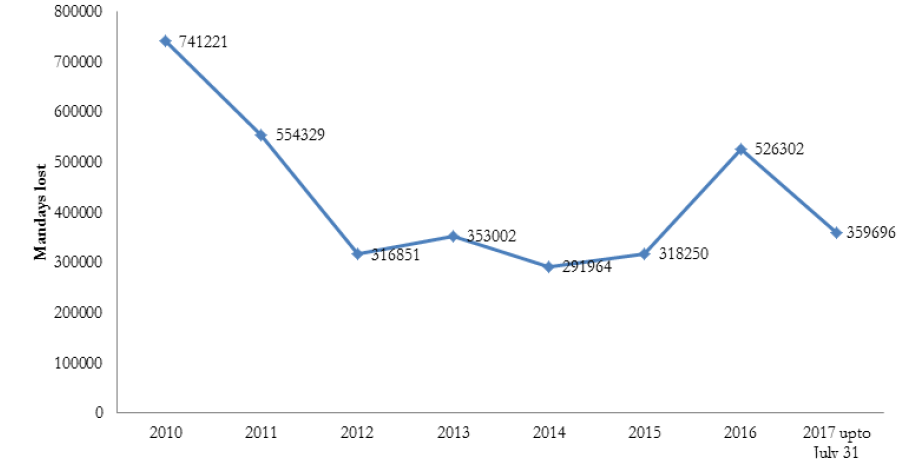

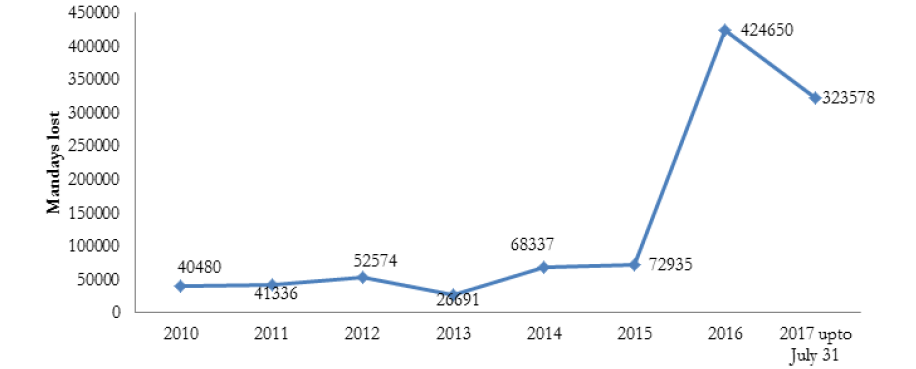

Mandays Lost Due to Lockout

The number of mandays lost due to lock-outs has been showing an increasing trend over the last two years. During the year 2014, total mandays lost due to lock out was 2.91 lakh, which increased to 5.26 lakh in 2016. However, total mandays lost due to lock out up to July 2017 is 3.59 lakh.

Figure 4.3.18 shows the details of man days lost due to lock outs in Kerala. This is despite the fact that for the last ten years, the number of working factories in the State has steadily increased.

Source: Labour Commissionerate

Source: Labour Commissionerate

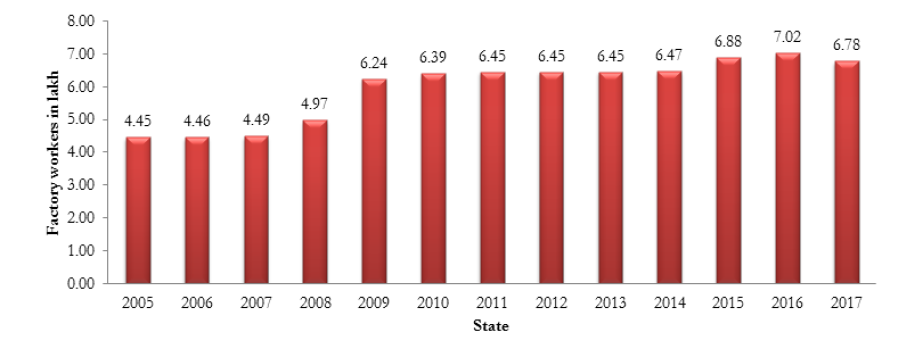

The number of working factories in the State in 2005 was 17,641, and this has now increased to 22,998. Subsequently the average daily employment creation in these factories increased from 4.46 lakh in 2005 to 7.02 lakh in 2016 and 6.78 up to July 2017. Figure 4.3.20 and Figure 4.3.21 shows the number of working factories and employment details in Kerala respectively.

Source: Labour Commissionerate

Source: Labour Commissionerate

Source: Factories and Boilers Department, GOK

Source: Factories and Boilers Department, GOK

Industrial Disputes

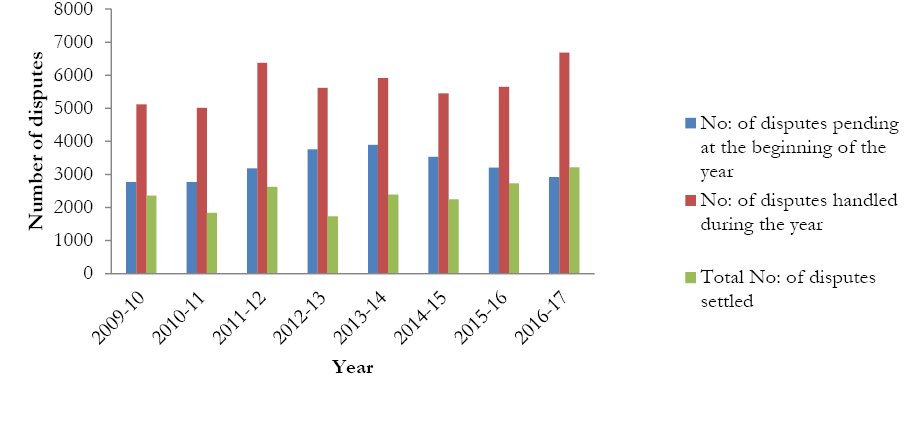

Providing a platform for raising grievances and settlement of the issues between employee and employer is an essential requirement for ensuring harmonious labour relations in the State. The Industrial Disputes Act of 1947 provides the legal framework for the same though it applies only to the organised sector. It also regulates layoffs and retrenchment. The number of disputes pending at the beginning of the year decreased from 3,890 in 2013-14 to 2,913 in 2016-17.

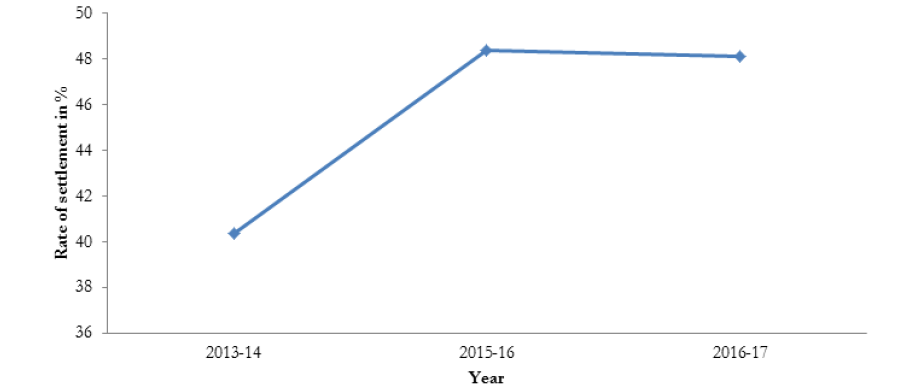

There is an improvement in the settlement rate of disputes as well. The total disputes handled during 2013-14 was 5,909 and the disputes settled for the same period was 2,384 which means that 40.3 per cent of the disputes were settled during that period. In 2016-17 the number of disputes handled was 6,682 and the number settled was 3,214 which works out to 48 per cent of the disputes. Details of the number of disputes in Kerala are given in Figure 4.3.22. Additional details are given in Appendix 4.3.61.

Source: Labour Commissionerate, GOK

Source: Labour Commissionerate, GOK

Strike: Section 2(q) of the Act defines the term ‘strike’ as cessation of work by a body of persons employed in any industry acting in combination or a concerted refusal, or a refusal under a common understanding of any number of persons who are or have been so employed to continue to work or to accept employment.

Lockout: Lockout, as defined in section 2(1), means the temporary closing of a place of employment, or the suspension of work, or the refusal by an employer to continue to employ any number of person employed by him.

Layoff: As per section 2(KKK) of the Act, ‘Lay Offs’ means the failure, refusal or inability of an employer on account of shortage of coal, power or raw materials or the accumulation of stocks or the breakdown of machinery or natural calamity or for any other connected reason to give employment to a workman whose name is borne on muster rolls of his industrial establishment and who has not been retrenched.

Source: Statistics on Industrial Disputes, Closure, Retrenchments and layoffs in India during the year 2013, Labour Bureau, Ministry of Labour, GOI

Safety of the Factory Workers

The Department of Factories and Boilers is a statutory authority that works to ensure the safety, health and welfare of all workers in factories and the general public living in the vicinity of factories through the implementation of various laws. The department enforces various programmes designed to ensure the safety of the workers. In 2017-18 (upto July 31, 2017), 28 priority inspections have been carried out in Major Accident Hazard (MAH) factories, 24 air monitoring studies were completed in hazardous factories, 1 medical examination of crusher factory workers and 112 inspections of hazardous factories other than MAH factories. The Department has been conducting training programmes not only for factory workers and employees but also for school children and the general public living in the surrounding areas. Details of industrial accidents and number of establishment/workers are given in Appendix 4.3.62 and Appendix 4.3.63. The programmes conducted Factories and Boilers Department are given in Appendix 4.3.64.

Rashtriya Swasthya Beema Yojana (RSBY)

The Rashtriya Swasthya Beema Yojana (RSBY) is a Health Insurance Scheme for BPL workers and their families in the unorganized sector. This was introduced in 2008-09 in all the 14 districts of Kerala. The annual insurance cover or in-patient treatment benefit is for a maximum amount of 30,000 for a family of 5 members including the worker, spouse, children and dependent parents (if included in the BPL family list). The annual insurance premium is fixed through a tender process. The State Government provides 40 per cent of the premium and administrative costs. The Central Government provides 60 per cent of the premium (including cost of smart card) directly to the implementing agency, CHIAK (Comprehensive Health Insurance Agency, Kerala). The beneficiaries are required to pay only 30 as registration fee.

Comprehensive Health Insurance Scheme (CHIS)

Comprehensive Health Insurance Scheme (CHIS) extends to all families other than the BPL families as per the guidelines of the Government of India. The non-RSBY population is divided into two categories: (a) those belonging to the BPL (poor) list of the State government but not to the list as defined by the Government of India and (b) APL families that belong neither to the State Government list nor to the list prepared as per the guidelines of the Government of India. In the case of families belonging to category (a), the beneficiaries are required to pay 30 per annum per family as beneficiary contribution towards a Smart Card. Under the CHIS, a family can avail in-patient benefit of upto 30,000 as in the case of RSBY. The entire premium is paid for by the State Government. Government and Private hospital wise details of the utilization of the scheme is given in Table 4.3.20. Given the fact that only empanelled hospitals (Public, Private and co-operative hospitals) are allowed to offer RSBY/CHIS benefits, the quality of services is assured. Further, the coverage is likely to be increased to 100,000. In addition to RSBY and CHIS, the State government has also introduced another scheme called CHIS Plus.

| Year | Number of patients, in lakh | Amount, in crore | ||||

| Public | Private | Total | Public | Private | Total | |

| 2015-2016 | 3.71 | 1.53 | 5.24 | 145.32 | 60.27 | 205.59 |

| 2016-2017 | 3.88 | 1.95 | 5.83 | 167.65 | 91.78 | 259.43 |

| Total | 7.59 | 3.48 | 11.07 | 312.97 | 152.05 | 465.02 |

| Source: Labour Commissionerate | ||||||

Aam Admi Bima Yojana

The Government of India has launched a new insurance scheme called the Aam Admi Bima Yojana (AABY) covering 48 categories of households in the country. This has been implemented in the State since 2007-08. As per the scheme, the head of rural landless families or one earning member in each such family will be insured. This scheme is also implemented through CHIAK. The premium under the scheme will be 200, of which, 50 per cent shall be a subsidy from the fund created for this purpose by the Central Government and the remaining 50 per cent is to be contributed by the State Government.

Employees State Insurance Scheme

The Employees’ State Insurance Scheme (ESI Scheme) of the Indian Government aims at protecting ‘employees’ in event of sickness, maternity, disability and death due to employment injury and to provide medical care to insured persons and their families. The comprehensive social security provisions are based on the ESI Act 1948. This scheme covers all the employees working in factories running on non-seasonal power that employ 10 or more persons, and factories not using power that employ 20 or more persons. It also includes those working in shops, hotels, restaurants, cinemas, road motor transport undertakings and newspaper establishments. Each insured employee and their employer are required to contribute a certain percentage of their wages to the ESIC every month. The ceiling wage rates are revised from time to time.

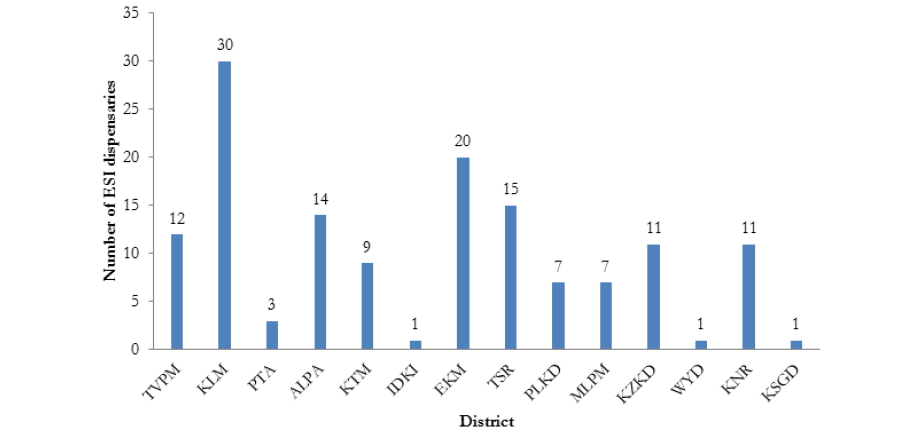

The ESI Scheme runs like most of the social security schemes. It is a self-financing health insurance scheme and the contributions are raised from covered employees and their employers as a fixed percentage of wages. The payments are to be made on a monthly basis. An employee covered under the scheme has to contribute 1.75 per cent of the wages whereas the employer contributes 4.75 per cent of the wages payable to an employee. The total contribution in respect of an employee thus works out to 6.5 per cent of the wages payable. However, employees earning less than 50 a day are exempted from making the contribution. All insured persons and dependants are entitled to free, full and comprehensive medical care under the scheme. This medical care is provided through a network of ESI dispensaries, empaneled clinics, diagnostic centres and ESI hospitals. Super speciality facilities are also offered through empaneled advanced medical institutions. Currently, six types of benefits are provided. These are medical, sickness, maternity, disability, dependants’ and funeral expenses. In Kerala there are 142 dispensaries and their distribution across the State is given in Figure 4.3.24.

Source: Directorate of Insurance Medical Services, Thiruvananthapuram.

Source: Directorate of Insurance Medical Services, Thiruvananthapuram.

Migrant Labour

The recent trend in the labour market in the State shows a large inflow of migrant workers from other States such as West Bengal, Bihar, Odisha, Uttar Pradesh, Chhattisgarh, Jharkhand and so on besides the neighbouring States. Working conditions of the inter-State migrant workmen are dealt with under the Inter State Migrant Workmen Regulation of Employment and Conditions of Service Act,1979. As per the provisions of the Act, the contractor has to obtain a recruitment license each from the State from which the workers have been recruited (Original State) and from the State where they are employed (Recipient State). Accordingly the contractor and the principal employer become legally obliged to ensure the implementation of the provisions envisaged in the enactment as the immediate employer and the principal employer respectively. But usually these workers cannot be brought under the purview of the enactment due to lack of statutory ingredients required to attract the ambit of the enactment such as an intermediary third party/contractor between the principal employer and the workmen. These workers are compelled to live in groups under unhygienic conditions near their working place with no access to proper health facilities.

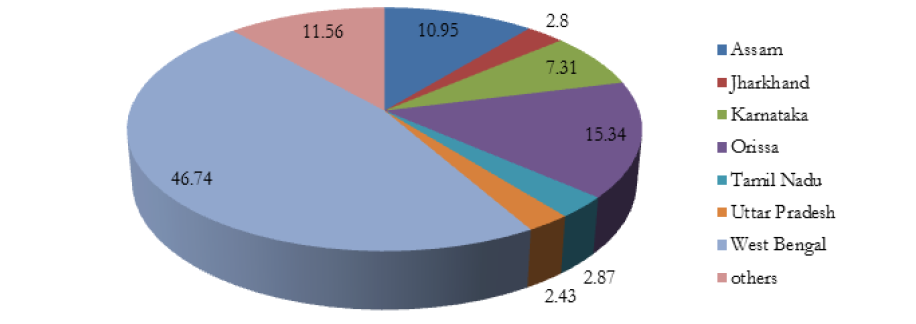

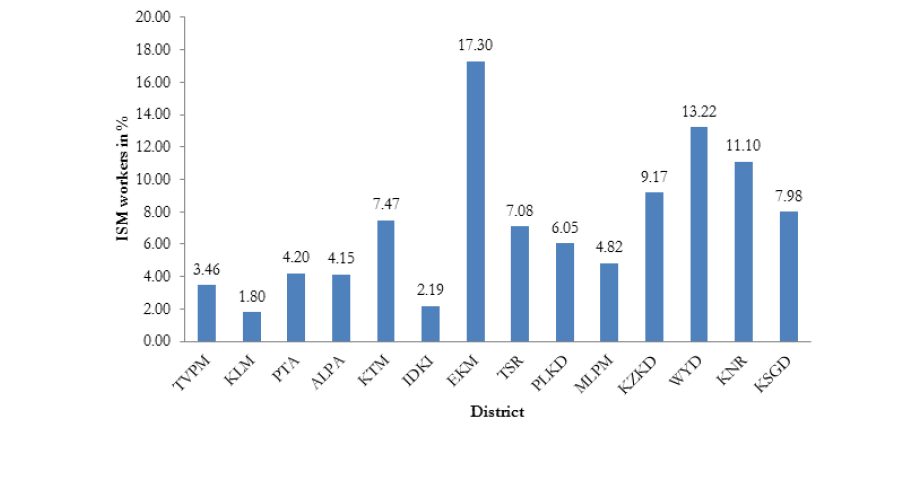

The distribution of migrant workers from different States is given in Figure 4.3.25. As shown in the figure 47 per cent of Inter State Migrant (ISM)workers are from West Bengal followed by Orissa (15 per cent) and Assam (11 per cent). The district-wise distribution of ISM workers in the State shows that Ernakulam has the highest proportion of 17 per cent followed by Wayanad with 13 per cent and Kannur 11 per cent. Figure 4.3.26 presents the distribution of ISM workers by district. Details are given in Appendix 4.3.65.

Source: Labour Commissionerate, GOK

Source: Labour Commissionerate, GOK

Source: Labour Commissionerate

Source: Labour Commissionerate

These ISM workers are engaged in different areas such as agriculture, construction, the hotel and restaurant industry, manufacturing and trade. It is seen that 60 per cent of the migrant workers are engaged in the construction sectors,8 per cent in manufacturing, 7 per cent in hotels and restaurants, 2 per cent each under trade and agriculture and the remaining 21 per cent are engaged in other activities.

Labour Force Participation Rate (LFPR)

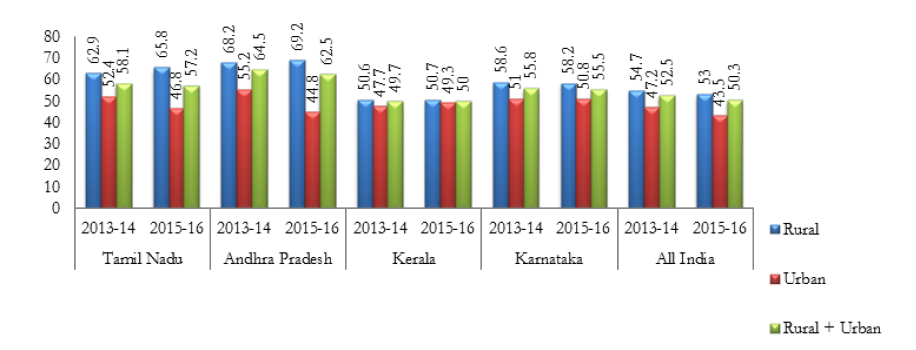

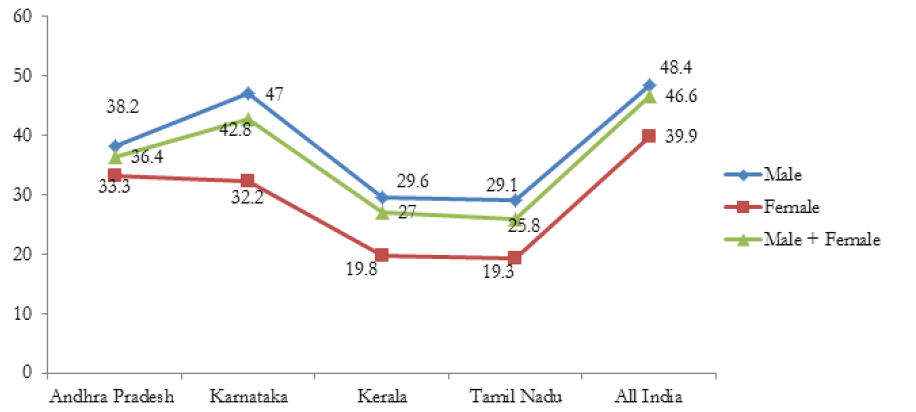

The situation of the labour force in Kerala can be gauged from the indicators such as LFPR, WPR, daily wage rage and trend in industrial relations. Among all the Indian States, low level LFPR remains a perpetual characteristic of the Kerala labour market. Apart from a slight increase of LFPR in the urban region, labour force participation has been constant over the last two years. As per the 5th Annual Employment and Unemployment Survey (2015-16) of the Labour Bureau, Ministry of Labour, Government of India, LFPR in Kerala is 50 per cent, a marginal increase by 0.3 per cent over the year 2013-14. Even if we are at par with the national average, LFPR in our neighbouring States is better at 62.5 per cent, 58.1 and 55.5 per cent in Andhra Pradesh, Tamil Nadu and Karnataka respectively. Similarly in rural areas, we are not only distant from the national average but also from the rates in neighbouring States of Andhra Pradesh and Tamil Nadu where it is 69.2 and 65.8 per cent respectively. Figure 4.3.27 shows the LFPR of Kerala and other southern States.

Source: Labour Bureau, Ministry of Labour, GOI

Source: Labour Bureau, Ministry of Labour, GOI

Yet another aspect of significant concern is the low female labour force participation rate. India’s rank in female LFPR is 136 among 148 countries. North eastern and southern States, in general, have a higher LFPR compared to low levels in northern States. In this regard, Kerala female LFPR is 30.81. It is lower compared to other southern States such as Andhra Pradesh (46.6 per cent), Tamil Nadu (39.2 per cent) and Karnataka (32.7 per cent).

Worker Population Ratio (WPR)

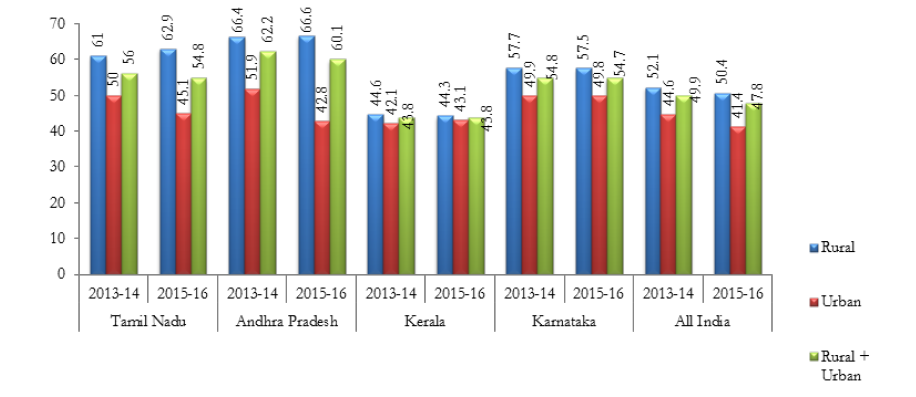

Worker Population Ratio (WPR) is an indicator used in the analysis of the employment situation and in understanding the proportion of the population actively contributing to the production of goods and services in the economy. The 5th Annual Employment and Unemployment Survey of the Labour Bureau, Ministry of Labour, Government of India shows a declining trend in WPR. The WPR is declining in India. The same trend is seen in the southern States as well. The WPR in Kerala is 43.8 per cent as against the all India average of 47.8 per cent. Among the southern States, the performance of Andhra Pradesh is admirable at 60.1 per cent followed by Tamil Nadu and Karnataka at 54.8 and 54.7 respectively. In rural Kerala, the WPR is reported as 44.3 per cent as against 66.6 and 62.9 per cent in Andhra Pradesh and Tamil Nadu. Figure 4.3.28 shows the trend of WPR in Kerala and the other southern States.

Source: Labour Bureau, Ministry of Labour, GOI

Source: Labour Bureau, Ministry of Labour, GOI

Self Employed Persons in Labour Force

Labour force engaged in self-employment in the State is 27 per cent which is 19.6 per cent lower than the national average. The male-female gap in self-employment labour force in the State is 9.8 per cent which is 1.3 per cent higher than the national average of 8.5 per cent. Even if self-employment among the labour force is high in Karnataka, the difference between male and female self-employed persons is high at 14.8 per cent. In Andhra Pradesh the gender gap is as low as 4.6 per cent. Figure 4.3.29 shows the percentage of self-employed persons in the labour force and the gender gap in Kerala and other States.

Source: Labour Bureau, Ministry of Labour, GOI

Source: Labour Bureau, Ministry of Labour, GOI

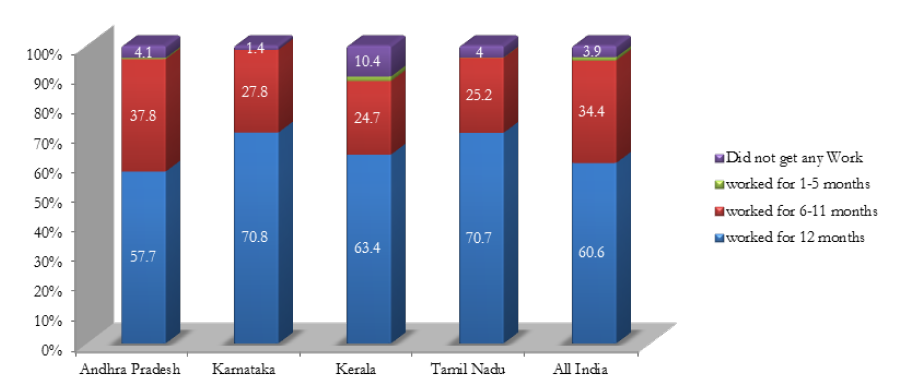

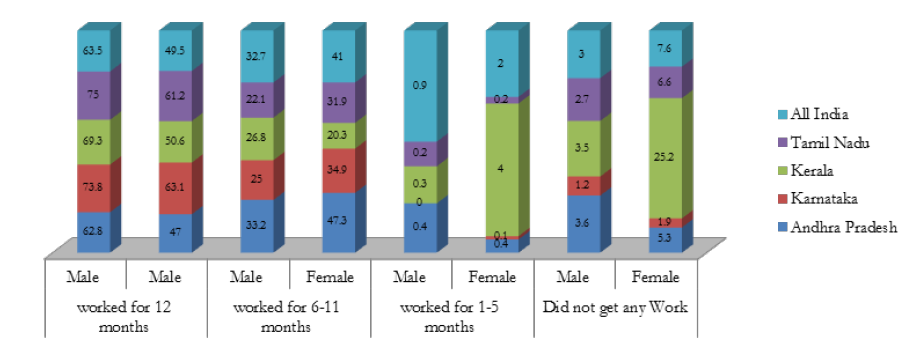

Workers Available and Actually Worked

Out of the total workforce available for 12 months, the actual percentage of workers engaged in work for 12 months is 63.4 in Kerala. In Karnataka and Tamil Nadu it is 70.8 and 70.7 respectively. Period wise classification in Kerala shows that 24.7 per cent of the workers were engaged in work for a period of 6 to 11 months and 10.4 per cent of workers were engaged in work for 1 to 5 months. Figure 4.3.30 shows the details of workers available for 12 months and the percentage of those that actually worked in Kerala and other southern States.

Source: Labour Bureau, Ministry of Labour, GOI

Source: Labour Bureau, Ministry of Labour, GOI

A gender-wise classification shows that male workers actually engaged in work available for 12 months was 69.3 per cent and female workers for the same period was 50.6 per cent in Kerala. Generally, male workers register more days actually worked than the female workers. The male-female difference for the workers available for 12 months and actually worked in Kerala is 18.7 per cent which is 8 per cent higher than Karnataka, 4.9 per cent higher than Tamil Nadu and 4.7 per cent more than the all-India average of 14 per cent. Figure 4.3.31 shows the male and female workers available for 12 months but actually worked in Kerala and other southern States.

Source: Labour Bureau, Ministry of Labour, GOI

Source: Labour Bureau, Ministry of Labour, GOI

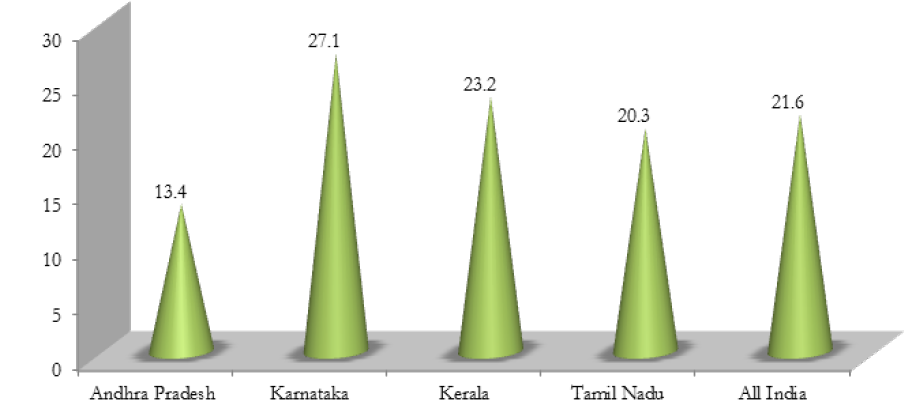

Workers Availing Social Security

Workers’ social security plays a vital role in the economic and social livelihood of every worker. A worker in Kerala is relatively better protected than those in other parts of the country. As per the report of the 5th Annual Employment and Unemployment survey, the percentage of workers except self-employed who avail social security in Kerala is 23.2 which is 1.6 per cent higher than at the national level and 9.8 higher than Andhra Pradesh and 2.9 per cent higher than Tamil Nadu. Among the southern States, Karnataka provides social security to 27.1 per cent of the workers except those are self-employed. Figure 4.3.32 shows the details of workers except self-employed availing social security in Kerala and other parts of southern India.

Source: Labour Bureau, Ministry of Labour, GOI

Source: Labour Bureau, Ministry of Labour, GOI

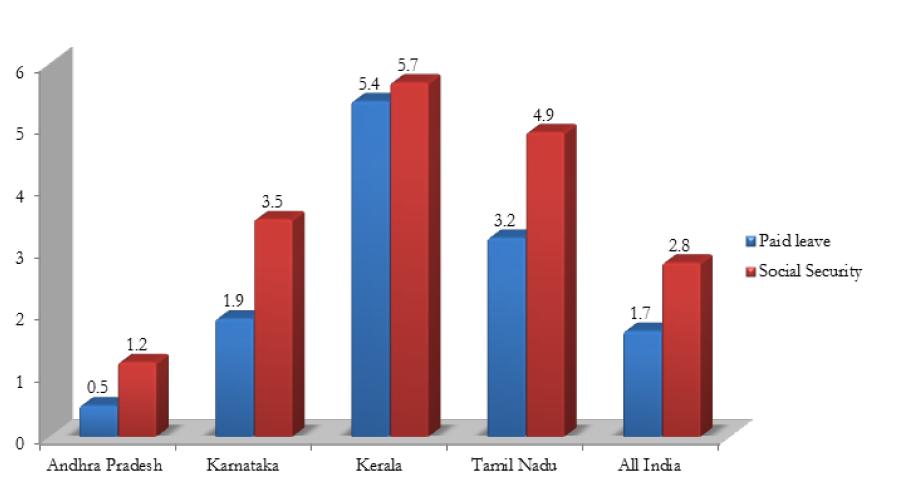

Social Security and Paid Leave for Casual Workers

Casual workers are not part of the permanent workforce, but they supply services on an irregular or flexible basis, often to meet a fluctuating demand for work. The level of benefits received by the casual workers is a pointer towards the labour-friendly approach of the society. Benefits received by casual workers in Kerala are relatively much better than in other States of the country. The casual workers who receive social security in Kerala form 5.7 per cent which is 2.9 per cent higher than the national average. In case of paid leave, 5.4 per cent of the casual workers in Kerala received the benefit which is 3.7 per cent higher than the national average and 4.9 per cent higher than Andhra Pradesh and 4.2 per cent than Karnataka. Figure 4.3.33 shows the percentage of casual workers received paid leave and social security in Kerala and other parts of the south India.

Source :Labour Bureau, Ministry of Labour, GOI

Source :Labour Bureau, Ministry of Labour, GOI

Outlook

Given the changing dynamics of the employment landscape of the State, the role of the Labour Department needs to be restructured in order to ensure a healthy employer-employee relationship in the long term. The issues confronting the vulnerable sections of the labour force are to be addressed through effective implementation of labour laws and focused welfare policies. The most vulnerable sections of the workforce viz. women, migrant labour and the large number of labour working in the unorganized or informal sector need special care and attention.